ree (or best offer)

Art has a complicated relationship with economics; it is both a place of resistance, and a site of collusion with economic forces. The exhibition 'FREE (or best offer)' brought together artists who use different strategies and formal approaches in their work to deal with the aesthetics of worth, asking the question: What does value look like?

Divya Mehra

Erica Mendritzki

CN Tower Liquidation

Claire Greenshaw

Annie Onyi Cheung

Ed Video, 40 Baker Street, Guelph

November 16 - December 14, 2012

Photos: Scott McGovern

Curator’s Essay

In late 2011, Cézanne's The Card Players sold for around $250 million to the royal family of Qatar. Estimates differ regarding the exact price, but what is certain is that this is the most expensive painting sold to date. What seems equally certain is that this staggering price tag, sooner or later, will be topped by yet another record sale.

Meanwhile, most living artists struggle to pay the bills—according to a study conducted by the Art Gallery of York University in 2009, the average Canadian artist actually loses $564 per year on his or her practice, while scraping together income from other sources to make an average of about $20,000 a year. Artists, then, are uniquely positioned to appreciate the fundamental absurdity of value. They stubbornly resist economic logic by working without financial gain, and they move in a social circle that comprises both the very rich—collectors, patrons, and benefactors—and the very poor—usually other artists. They invest countless hours of volunteer labour into building an art community—but they do so not only out of love, but also with the hope that working the scene will eventually lead to gallery representation, or a sale, or a well-paying part-time job. They understand how preposterous it feels to set a price for a work of art, when hours and money invested mean almost nothing, while the artist’s name, the place of exhibition, and the ambitions of maker, exhibitor, and buyer mean almost everything.

It makes sense, then, that many young artists might be interested in engaging with the fundamental absurdities of our economic systems. FREE (or best offer) brings together a diverse group of artists, each of whom actively explores the aesthetics of worth, raising questions about what role actual objects play in an economy and an artistic culture that is increasingly idea-driven and immaterial. Although their conceptual strategies and formal approaches differ, these artists share an interest in the basic question: what does value look like?

Art’s ability to rehabilitate discarded objects is a recurring theme. CN Tower Liquidation, an artistic collaboration between Sebastian Butt, Xan Hawes, and Charlie Murray, offers a kind of recycling service: for the cost of labour and materials, CN Tower Liquidation will shred your possessions—precious or otherwise—and cast them into a resin cube. Among other objects, a VHS recording of the 1990 film Ghost, a poetry book, and a balloon that was previously part of an installation by Canadian artist trio General Idea have all been broken down and cubed. This is a gesture that at the same time combats and perpetuates nostalgia—the object is both destroyed and preserved, and their cubes mingle sentimental value with artistic capital. CN Tower Liquidation’s promotional tactics parody the hard-sell stylings of low-budget cable television ads, operating in stark contrast to the discretion that marks most art world business transactions.

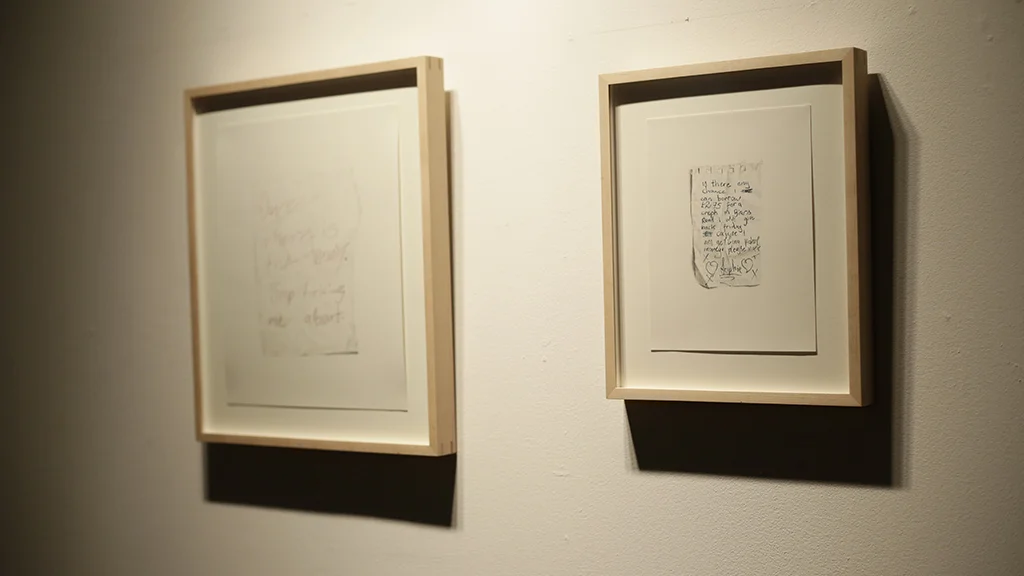

Clare Greenshaw’s drawings Any Chance and The Money offer alternative models for talking about the circulation of capital. They are trompe-l’oeil depictions of notes found by the artist on the street, both of which include requests for money. In Any Chance, someone named Sophie asks “Is there any chance I can borrow £2.75 for a creph in Biars Road I will give back friday cause I'm getting poket money please Sophie xxx.” The Money, on the other hand, is more threatening: “Dave where is the money. Stop fucking me about.” In both pieces, the scrappiness of the original notes contrasts starkly with the painstaking hyperrealist rendering. By drawing the discarded objects, Greenshaw re-invests them with aesthetic value: we’ll never know whether or not Sophie got her “creph” or if Dave paid up, but the drawings are beautiful in either case.

Annie Onyi Cheung’s work Finational generates aesthetic capital out of strips of newspaper taken from 2008 financial news pages. Cheung has woven the thin bands of newsprint into a burial flag, folded in accordance with the American army funeral ritual. The woven flag is accompanied by a video documentation of a performance of the flag-folding ritual. The wide-spread loss of paper wealth during the 2008 financial crisis, symbolized both by the ceremony and the real-life decay of the non-archival newsprint, is dealt with ritualistically, channeling the trauma of economic decline into artistic performance. The piece uses army aesthetics in order to problematize the West’s near-religious belief in the importance of militaristic and economic strength, while also eulogizing outmoded models of social organization.

Divya Mehra also addresses the interplay of nationalism and economics in Here's to Us (Who wore it best?), a piece consisting of a fake gold watch set to Indian Standard Time, and a fake silver watch set to Pakistan Standard Time. Like competing celebrities, the “Indian” and “Pakistani” watches both demonstrate an ostentatious love of bling, but they assert their difference through a half-hour time gap. Because both watches are fakes, neither “gold” nor “silver” is inherently more valuable—the answer to “who wore it best?” is simply a matter of taste, or personal allegiance. Neither is more authentically valuable than the other.

Erica Mendritzki’s work Tricia, like Mehra’s watches, also addresses issues of class and culture from an aspirational angle. Tricia is a framed photograph of a bottle of cheap perfume. You can tell what it smells like just by looking at it: the bottle’s fake plastic lid and over-zealous cursive lettering makes it clear that this is a scent that marks the wearer as unsophisticated and poor, though promising to exude glamour and attractiveness. We get the sense that no one quite fell for this promise, because Mendritzki found the perfume at a thrift store. Hand-written lettering on a fluorescent green price tag indicates that Tricia was “Free”: too pungent to merit a price (even in a store that charges for used underwear), but still too valuable to be thrown out altogether. Tricia exists in a purgatory of values, suspended between waste and commodity. By photographing Tricia, Mendritzki has turned the bottle into an artwork, and thus, into an emblem for artistic freedom which is either immensely valuable, or entirely worthless, or both, depending on your point of view.

Artists, like the work they produce, have an ambivalent relationship to the economic system that sustains them. FREE (or best offer) can’t liberate its audience from the restrains of a capitalist system, but it does offer an occasion for artists and viewers to exchange ideas, instead of (or as well as) money. This might be a way to be free, at least until there’s a better offer.